Chapter 13: Han Zi

Chapter 13: Han Zi

It was between four or five in the morning the first day I woke up in Taizhou, the summer after sixth grade. I remember lying there, jetlagged, knowing it was too early to get up, staring at the same spot out the window. It was the edge of an overhanging ledge outside of my Waipo’s home. I did not move, looking at the clean edge against the brightening sky until I began to hear the sounds of gongs and cymbals and the chanting of elderly women as they practiced their dance routine. Perhaps it was the soft light of the morning sun on that overcast day that removed all gradations from the green and gray slats underneath the ledge. It felt unreal to me, as if I were looking at a painting. I wondered if the previous school year had been just a bad dream.

Waipo took me to walk around the old stadium. It was still early in the morning, slightly foggy, not yet warm. My previous memories of Waipo’s home had been from a time when I was so small that I had almost forgotten that her apartment was located in the almost hundred year old stadium. The morning dew glistened on the rust covered gates when we entered the track, walking past the almost crumbling stage. There were others also here to walk and stretch, mostly senior citizens, though some brought their grandchildren as well. I continued to feel the anxiousness from feeling the gaze of the crowd, yet here it began to slightly dampen. No one seemed to pause and stare at me, not even taking notice as we walked past the narrow corridors to the other side of the gate. No unkind thoughts hung in the air here.

Breakfasts with Waipo and Waigong would become my favorite part of the summer I spent with them. The early morning walk across the stadium and along the alley would become our routine before sitting down to gansi, a dish of soft, thin, delicately sliced tofu noodles that sat in a bed of light sauce and underneath a pile of ginger, vegetable bao so fragrant that we could smell them across the hall, and hearty bowls of wontons in thick, milky fish broth that had been simmered for hours. The breakfast, which they called “morning tea”, was served in a banquet hall that Waipo and Waigong seemed to be regulars at, as they often greeted friends walking in. We sat at the side of very large round tables covered in a thin plastic film, sometimes with strangers. Tea was poured from old oversized Thermos bottles that waitresses would carry like a bucket. Every bite had a kind of softness and sweetness that I would only learn decades later was unique.

In the first few weeks of that summer, I would often watch tv on Waipo’s old television set when I was bored, flipping through the six or seven CCTV channels. One of them played cartoons, but only occasionally. Some days it was Digimon Adventure. Some days it was Crayon Shin Chan. It was always dubbed in Chinese. The channel would play an episode or two, then switch to a blue test screen with a grid of strange patterns. In the background would play the same Richard Clayderman piano piece, on repeat.

During those months one of my aunts from Waigong’s side of the family came to Waipo’s house three times a week to tutor me, telling me that she was a teacher and my mom had vaguely asked her to help me work on my writing. I think my mom was still in shock over my abysmal grades the past year and wanted to do everything she could to keep me from falling behind. My aunt told me her English was very good, and for the first week asked me to write her five pages of anything, just so she could see my skill level. I remember sitting in my Waipo’s rosewood chair with a clipboard writing a few pages of my experiences coming off the plane and seeing the Shanghai Airport. After reading through a few days later, my aunt remarked that this was better than anything she could write and offered to tutor my Chinese instead. She smiled at me as she said this, remarking to Waipo that I was obviously well educated. I felt a curdled sense of guilt that I could not explain.

We went through basic vocabulary words in Chinese, stumbling often. Even though I had learned from my mom and grandma the previous summers, I realized that I had never read or written Chinese outside of lessons. I found that I barely recognized most characters, and couldn’t remember the correct order of strokes. My aunt started from the easiest characters and had me practice using words in sentences. Write down your thoughts, and you will improve, she said. But I realized that I didn't know which language I heard in my head anymore.

Waipo walked me to her neighbor’s house everyday, down a dusty birch lined street filled with the noises of near constant construction, so that I may practice the piano for an hour. My mom had packed me all of my sheet music books, and my piano teacher had marked assigned pieces to practice. I didn’t really want to play most of my assigned music and after a week began to sight read other pieces I found as I flipped through the books. I felt a little guilty, as if I’ve found yet another way to disobey my mom. Waipo never questioned if the pieces I played were the ones I was supposed to or not, preferring to sit and listen with her eyes closed. By the end of that summer I had doubled my repertoire.

In July, Cousin Xuechen came to visit for a day. I don’t remember what we did but I remember she gave me a box set of the anime Case Closed, dubbed in Chinese. The weeks that followed, I binged the show though Waipo complained that it was too graphic. As I watched I began to notice that the way I spoke Chinese was different from the Chinese I heard on screen, often stilted and somewhat slow compared to the characters in the show that spoke quickly, like air being let out of a balloon. When I asked Waipo why this was, she said there was nothing wrong with the way I spoke, other than that I sometimes echoed my grandma’s mannerisms. Soon I began to repeat words and expressions I heard, Waipo complaining that I learned too many bad words.

My maternal grandparents lived in a small first floor apartment on the grounds of the old sports center. The home was often dusty, smelling like old rosewood, an austerity that came with affection. I would often run my fingers along the walls feeling the texture of peeling paint and concrete. The kitchen and bathrooms had windows that looked into the rest of the home, the door frames mismatching with the seams of the walls, being later additions. Everyday I would wake to the sounds of morning exercises and street hawkers. There were a few days I stayed with my mom’s older brother Jiujiu and auntie Jiuma in their two story apartment on the top floor of a building in the new part of town. It was a different kind of language, one filled with the scents of new Scandinavian furniture mixed with the reflections of glass and the hum of an AC unit. It felt like stepping through a time machine, the shiny neon signs of the gigantic shopping center that Jiuma would take me to when she bought groceries. I felt bad preferring the automatic doors to the creaking stairs, the air conditioner to the fan that coughed dust. I was suspended between two Chinas, not knowing which was more true.

I remember a small incident, my last weeks in Taizhou, when I went with Waipo to the market. Since my first week there I had been curious by the sight of various rickshaws I saw riding up and down the streets. They were two seats across an axle of a set of very large wheels, underneath a colorful awning, pulled by a cyclist. These rickshaws reminded me of rides at Disneyland, the way passengers looked out at the open air as they slowly rolled along. Waipo suggested that we take one and I became incredibly excited. We sat there without a word, as I looked out into the street past the fruit vendors and toy shops. The driver pedaled standing up, a tall and very thin elderly man with dark wrinkled skin, so browned by the sun that he looked as if stitched from worn leather. As we rode along, the triangle of sweat began to widen on his back and his breathing filled the silence. Pushing down an uncomfortable feeling in my throat, I looked away, keeping my eyes on the gutter below.

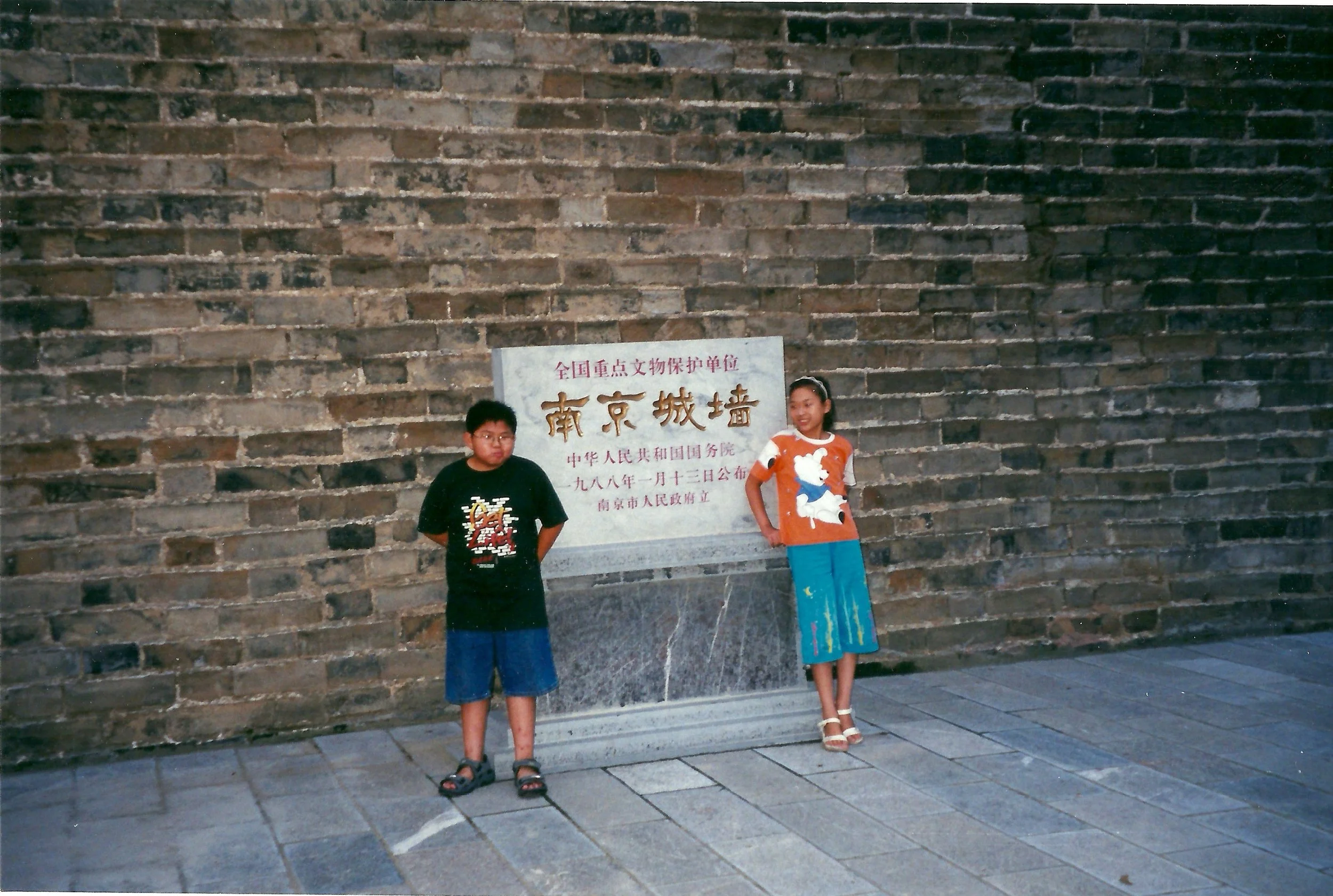

For the last few weeks, in August, my dad picked me up and took me to Nanjing. Dabaima, my aunt on my dad’s side, didn’t want me to be lonely since my dad had work during the day. She introduced me to her friend’s daughter, Faye Chen, who was my age. Faye was slightly taller than me, very pretty, and extremely pushy: her mannerisms reminded me of those 1950s auctioneers I’d seen in black and white films. Everywhere we went she was snacking on something, pestering her mom to buy her more treats. Despite it, she stayed thin, yet didn’t make fun of my weight like most kids that year. She said she wanted to get better at English but was tired of the workbooks and extra homework her mom made her do, even outside of school.

Dabaima took us to a nearby park where we met the son of another friend of hers. She wondered if I’d rather play with a boy instead. The three of us hung out for a while, but all afternoon he kept calling me “hey you, American.” I told him I didn’t like that. He said, “Well, you are American, aren’t you? You even talk a little different.” Faye followed me as I stalked away and sat on a rock, sulking. “What’s wrong?” she asked. I asked if my Chinese was really that bad. “No,” she said. “Maybe a little old fashioned, but you look just as Chinese as we are. Hey, let’s ditch that guy. There’s a place nearby that’s cool.”

The cool place was the night market. I stared in awe as Faye grabbed my hand and led me through a cacophony of lights and noise: vendors selling street food, DVDs, toys, most of it counterfeit. I stopped at one stall to look at a toy and asked the price. “Twenty yuan,” said the vendor. I was about to take out my wallet when Faye said it was too steep, that it wasn’t worth more than ten. I was ready to say it was fine, I’d buy it anyway, when she stepped on my foot and said loudly, “He doesn’t want it, are you kidding? He grew up in America, have you seen the toys there? No one from there would buy this junk.”

Then she dragged me away. I was about to tell her I still wanted it when the vendor called after us, “Fine, fifteen!” Faye smiled like she’d just won a game.

We went to Sun Yat Sen park with Cousin Xuechen the next day, taking the taxi up the winding mountain road. On the way there, I told the driver, half proud, that I was American. He laughed through his nose. “America”, he said, like he had just swallowed bitter medicine. Spitting out a window, he said “I’m glad 9/11 happened. You people bomb other countries all the time. You just can’t stand it when it happens to you!” I didn’t know what to say as Faye berated him for being so rude, half yelling, “hey my friend is not the one who bombs people!” Cousin Xuechen kept quiet, awkwardly staring at the ceiling, half moving her mouth as if to say something. It was strange to realize I could be hated for what I wasn’t, in a place I thought I was from.

We spent the day hiking, eventually stopping at a small themed attraction called “bridge world” with various kinds of strange bridges that hung over a creek. Some were made of rope, blocks of wood suspended from cables, others were made of steep logs zigzagging above the water. The most unusual bridge was a literal human hamster wheel that rolled along a set of tracks. Faye and I sprinted to the hamster wheel as my cousin tried to catch up behind us. She leapt down from the steps and landed badly, spraining her ankle. Faye and I ran through the wooded trails in the direction of the front gate, looking for somewhere to buy an ice pack. I stopped and asked for directions at a booth, a woman pointing to a map written in Chinese. I nodded blankly, unable to read any of the characters. I felt my ears were filling with cotton, unable to hear what Faye was saying and she led me away telling me it was okay, she knew where to go.

After the new school year started, weeks after I came home, I got a long distance call from Faye. She told me it was one of the best summers she’s ever had, telling me she hated school, wishing vacation never ended, asking if I’m coming back next summer. I couldn’t find many words as she talked, quietly laughing to myself unable to contain the elation of my first time talking on the phone with a friend. After she hung up, I decided that I wanted to write her a letter in Chinese, maybe on a postcard.

I stared at the blank page for a very long time before I gave up.